Frank Farina was my music teacher in high school and, maybe more famously around the regional high school band scene, our marching band director at North Allegheny Senior High School (NASH) in Wexford, PA, a suburb of the city of Pittsburgh. He died on August 15, 2012.

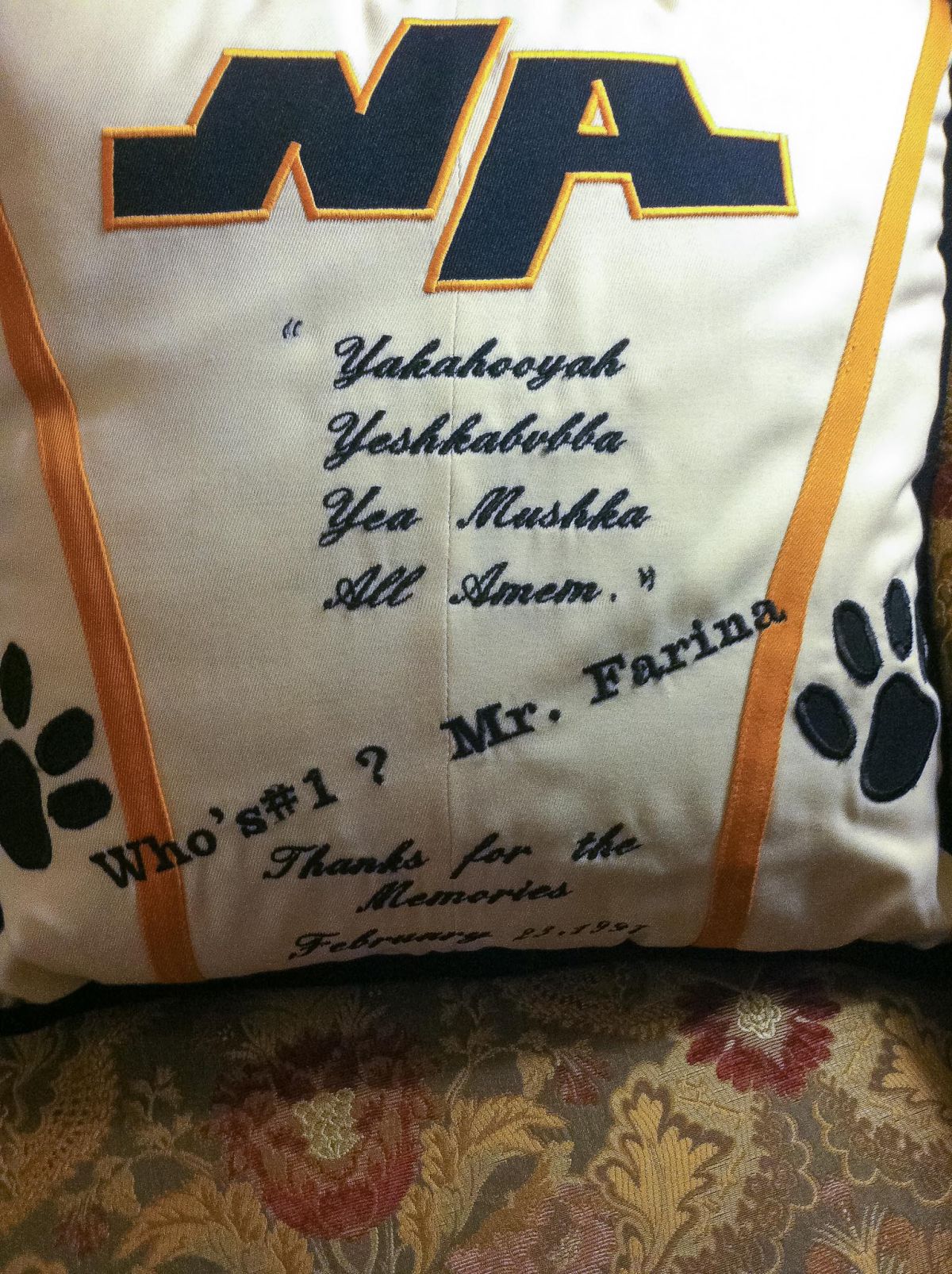

Mr. Farina had a cantankerous yet magnanimous aura, he was charming in his own particular way, hard to ignore and, if you were a musician, hard to avoid – he ran the school's entire music program. He was almost universally loved by the students who passed through his music program. Mr. Farina was idiosyncratic, a little grouchy, but full of good intentions and incredibly persistent about them. He was a charismatic, larger-than-life presence, a near-mythological man in most of our young minds. He was old-school, obstinate, and frequently delivered odd, brilliant aphorisms approaching the complexity of koans. "It's a shot and a beer town!" was just one of them.

My friend Fritz, fellow NASH graduate, and I met up at The Shanty, a bar here in Brooklyn, on the 16th to celebrate the man, contemplate his wisdom, and toast to his legacy with shots and beers.

Fritz and I played in Mr. Farina's marching band, jazz band, and wind ensemble together, out of shared love and obsession with music, but were at odds then in our personal interactions. We became friends only after high school, only after running from cops together when a party were were at was broken up in the summer of 2000. (That's another blogski for another time.) We started playing music together later that summer, with other kids from the band program, and have worked together on projects ever since.

Fritz moved to California in 2004 and I stayed in Pittsburgh. We stayed in touch. He and I both moved to NYC in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Now we both work at the same office. Fritz is the assistant for Nico Muhly. I'm archiving manuscripts and ephemera for Philip Glass. Had it not been for Mr. Farina, and our time playing in his bands, I doubt either of us would be doing this these things.

In spite of being difficult, deviant kids, Mr. Farina took time to make better musicians and people out of the two of us. Although he told me once I had no finesse (something that sticks with me to this day when I practice), he still invited me to play in his bands. In my senior year I was under Mr. Farina's supervision for five periods daily, in five separate bands. Each band had a it's own catalog of music, it's own level of difficulty, and it's own sort of kid in it.

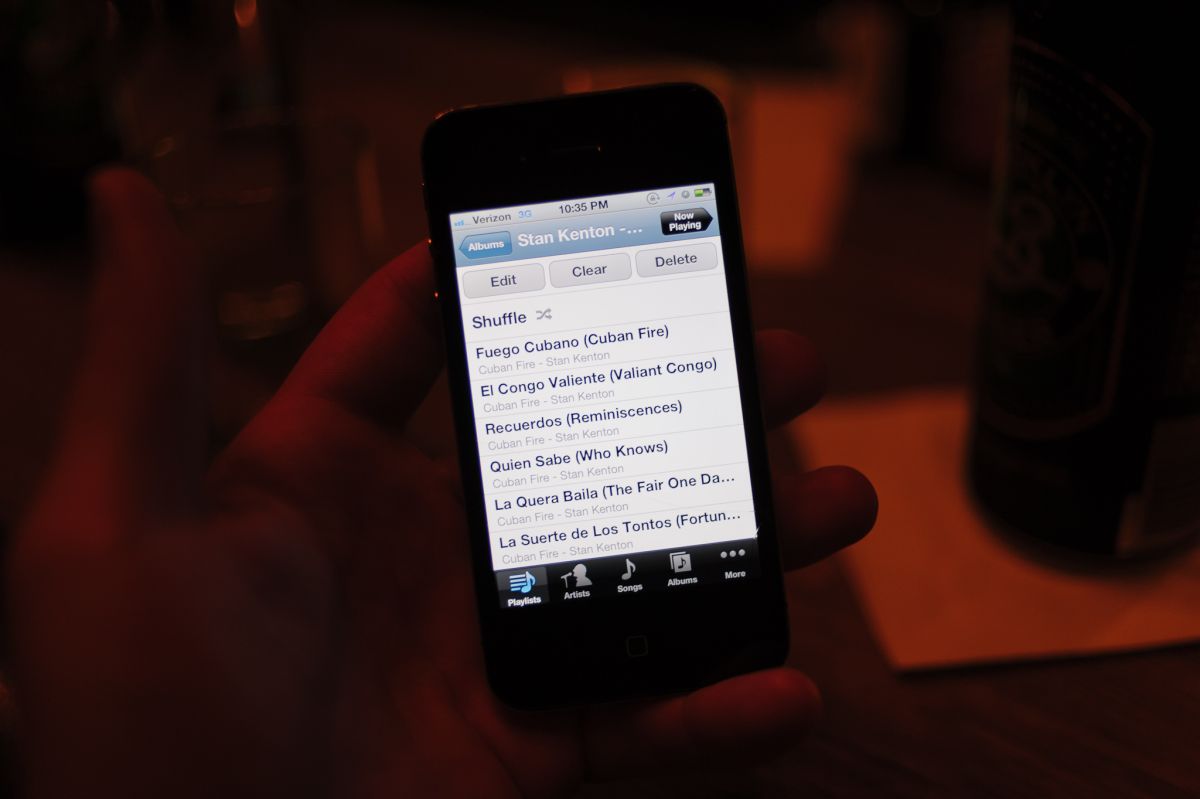

I was in the marching band (for coördinated nerds), the wind ensemble (for the dedicated or well-practiced), the concert band (for the less enthusiastic), pep band (for sports lovers with no athletic skill) and jazz band (for the out-there players). We played a ton of Stan Kenton and Maynard Ferguson tunes in Jazz band. I got a diverse education in music that way. It prepared me for playing and appreciating the wild variety of music out in the world.

I've applied that education. I’ve drummed on a number of albums, sat in with dozens and dozens of musicians (some of which also played with Maynard Ferguson, completing a circle of awe in my mind) at jazz sessions, showed up on a few film soundtracks and have generally kept music performance in my life for the past 14 years.

I have nothing but respect for Mr. Farina now, though there was plenty of reciprocated antagonism in the day. More than once I was put in my place.

"If the shoe fits, put it on."

"If the shoe fits...” he'd start in a rehearsal. This would prime our attention to our mistakes. These mistakes could be in our playing, actions, haircuts, or personalities, whatever. We'd obligingly reply: "Put it on." If we didn't complete the sentence, he eventually would. You could generally, safely assume if Mr. Farina was giving this line to you, the shoe already fit and you should wear it.

I can't really count how many times he said that one to me, or how many shoes I wore. Sometimes I earned it for the way I played. Most of the time it was stern encouragement to confess about another obnoxious thing I'd done, a lock I shouldn't have picked, a closet I shouldn't have raided, or the enthusiastic harassing of the underclassmen that was then my civic duty.

So, as part of the tribute, I took a ruler to the Shanty. This allowed both Fritz and I to measure our shoes for verification of fit.

"It's a shot and a beer town!"

Mr. Farina would shout "it's a shot and a beer town!" in moments of more existential frustration. It was his way, I think, to criticize simplicity – or simpletons – in either the school system, or Pittsburgh and its cultural predilections, which generally begin and end at Steelers football and dive-bar-grade rock music. Our school system, like so many others, doted its time and resources on athletics programs. In the years since I've graduated, it's only become more absurd. But that's, the economy, these days, America, or some other excuse for you. Send the blame where you'd like. If the shoe fits, put it on, I guess.

In 2010, some time after I got the archving job, Mr. Farina ran into my mother. Of Fritz and I he said, "I never thought I'd know people who worked with people like that."

That sentiment is dubious. Neither he or Fritz or I saw it coming of course. I'm pretty sure I just got lucky, but we're both sure Mr. Farina had to believe it was possible. He believed his students could achieve great things – if he could only prevent us from fucking up too much. That perspective made him an effective, irrepressable teacher, the sort of teacher you were willing to make mistakes in front of because you knew it wasn't going to be permantently held against you. Mr. Farina's perspective on students as people was in tune with the nature of playing music: nobody gets things right on the first try. Fucking up happens in music and life. So does getting better. In music you play and make mistakes, you practice to reduce and remove mistakes. Then you practice for the virtue of improvement in itself.

Fritz likes to quote another teacher of his, Donald Wilkins, who once said "redemption is in the next note." It's a perspective, like Mr. Farina's, that's almost outdated in the days of the internet, where the long tail of a mistake exists for eternity, for the world to view.

A few days after Mr. Farina's passing, I was on a job in Pittsburgh. My parents and I went to the viewing in West View, another Pittsburgh suburb. I saw a few old friends there, talked with other students and my teachers, all of whom were mildly surprised that I stayed out of trouble. Thanks for the support, everybody.

The wait at the viewing was long. Mr. Farina played a part in hundreds and hundreds of lives in his decades of teaching – around 300 per academic year if you only account for the students in the marching band. The line snaked out the door and into the parking lot. I heard some people waited for two hours.

Mr. Farina always was good at drawing a crowd.